Monica Valeria Goncalves, 47, has two university degrees. She works as a legal adviser in Brasilia and is married to a judge.

Por Noemia Colonna, da BBC

She frequents expensive restaurants and exclusive social events, and lives in one of the Brazilian capital’s most privileged neighbourhoods.

In short, her life is very similar to that of the rest of her social class – the top 1% of Brazilian society.

The only difference is that she is black. That makes her part of the majority of the Brazilian population – 53% are black or mixed-race according to the latest census – but in a minority among the upper class.

She is often the only black person at parties, restaurants or any other social or professional events – apart from the waiting staff.

When she attends conferences with her husband, people assume she is his secretary.

“People make that mistake a lot,” she says.

But the incident that hit her hardest took place 22 years ago, while she was spending her honeymoon at a beach resort.

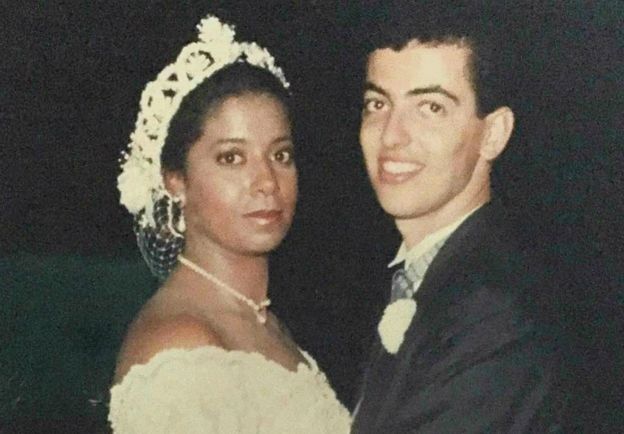

Monica Goncalves and her husband Carlos Augusto Nobre married 22 years ago

“A man touched me and openly propositioned me. I was frightened and screamed at him. He apologised, saying that he thought that I was with a white man working as a prostitute.

“It didn’t occur to him that the man was my husband, who was married to a law graduate with an independent income.

“It wasn’t possible, in his mind, for a black person to be at that place.”

Sociologist Emerson Rocha from Brasilia University says that, contrary to what many believe, racism in Brazil does not vanish once you become wealthier.

“It’s the opposite. Once black people leave their ‘natural space’ they are more vulnerable to racism, they become a foreign body in a predominantly white space.”

Ms Goncalves was the only person in her family to climb the social ladder. To do that, she had to overcome various hurdles.

“All my life, I’ve had to demonstrate that I was very good at what I do. If I didn’t do this, I’d be judged both on the quality of my work and on the colour of my skin,” she says.

‘Prepared for battle’

Film-maker Sabrina Fidalgo has a different perspective. She was born rich. “My parents prepared me for war,” she says.

Sabrina was the only black girl at ballet in Rio

“Before I started primary school, they warned the nuns that if I was the victim of any racism they would vocally protest.

“They insisted that the school was responsible for making everyone aware of racism. They were proactive, not reactive.”

But at secondary school, things changed and she remembers one teacher who would openly tell jokes about his racist grandmother.

“I told him how bizarre that was. He apologised and stopped,” she says, crediting her parents for the courage to fight back.

“They told me from a young age about the history of Africa, about our role in society. They told me how beautiful my hair and my skin colour were.

“They told me never to feel ashamed and that I could be anything I wanted, a doctor or a ballerina,” she says.

Sabrina credits her parents with teaching her to fight back

Ms Fidalgo believes it is important that people talk about racism, but warns that black people should not be constrained by it.

“What bothers me about this narrative is that it implies that only oppressive experiences are legitimate.

“In a way, it reaffirms racism by suggesting that we black people only deserve something after being subjected to pain and humiliation.”

Emerson Rocha agrees. “It’s important to denounce racism, but the positive experiences have a role to play. Stories like Julio Santos’.”

Success story

The son of a domestic worker, Mr Santos, 50, had to work washing cars from the age of 13.

Today, he is an engineer who owns a successful recycling company.

“I have businesses in New York where I often meet black entrepreneurs. In Brazil, it’s a different story.”

PHIL CLARK HILL/BBC BRASILImage captionJulio Santos went from washing cars to being a millionaire

A story that Ms Goncalves thinks is only slowly changing.

She is the mother of an eight-year-old girl and she would like to see a more equal society develop more quickly.

Her daughter Leticia studies at a traditional, bilingual private school, where she is also an exception.

“There are more than 200 children, but only two are black: my daughter and another girl, who is the daughter of a domestic worker,” Ms Goncalves says.

LEOPOLDO SILVA/BBC BRASILImage captionMonica Goncalves, her husband Carlos and daughter Leticia live in Brasilia’s richest neighbourhood